Defending the commons, the case of free music

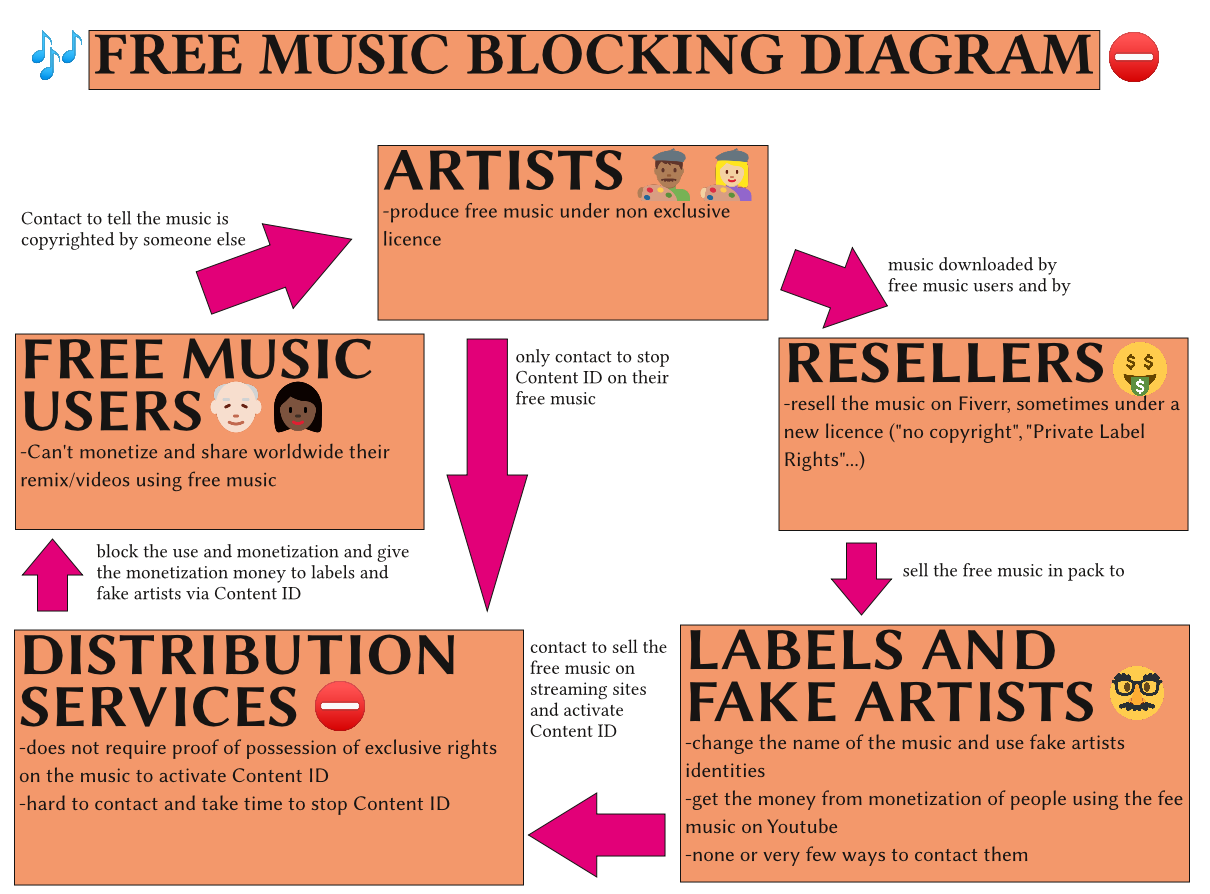

Diagram summering the actual situation of free music on the internet. Courtesy of Rose, Creative Commons 0.

Pour la version française de l'article, cliquez ici.

Abstract : Rose, a creative commons 0 license-free music composer, investigates her own music being blocked and monetized by fake labels. She discovers the website Fiverr, a virtual market on which some entities sell her music among other librarian-creators’ works. The conditions of use that are attached to creative commons 0 license free works aren’t mentioned during the sale, notably the rule prohibiting activation of the Content ID tool that blocks the diffusion and monetization of music on streaming platforms through musical distribution websites.

I am Rose, a creative commons 0 license-free music composer. I have produced over two thousand musical pieces and 99% of them are for everyone to use (even commercially) under this license.

The reason why I’m writing this article is to talk about the investigation I conducted about the privatization of license-free music and the steps that led me to investigate.

If this sounds like something obscure or of little impact on most people’s lives, I have to say it has, in fact, numerous consequences on the diffusion and use of knowledge and it’s the evidence of some serious gaps in the protection of common resources.

I have to clarify beforehand that I am not a legal expert nor a journalist. I have no training in either of these areas.

Creative Commons licenses might be unfamiliar to you and I will now try to explain them briefly.

These licences allow creators willing to do so to soften possibilities of use of their creations. For example, some Creative Commons licenses allow distribution, remixing, and commercial use of creations, which is something a copyright wouldn’t allow.

The Creative Commons 0 license is the closest one to public domain. Usually, depending on the laws, you have to wait until the death of the creator and add a few decades before their license/creation is elevated to public domain. Under the creative commons 0 license, without the creator being dead, the creation is mostly free to use. There are a few constraints though, notably that this license doesn’t prevail over the legislation of the country where the creator resides.

Creative commons licenses can’t be used in any situation. In this specific situation, it is strictly forbidden to use Content ID on Creative Commons licenses.

Now let’s talk about Content ID, one of the lead actors of our story.

We’re on the Internet and we’re trading works to remix. Some people choose Creative Commons, others choose classical copyright as a license for their creations. To defend copyright and related rights in 2007, companies such as Viacom, Mediaset and Premier League—among others—pressured YouTube (then recently acquired by Google) to create a tool called Content ID. This tool allows YouTube to detect copyrighted content (videos, music, etc.) and to restrain its use on its platform, by blocking the content or monetizing it and sending the money to the rights owners or their relatives. Massively used by the music and video industry, it has its load of absurdities regarding copyright but also public domain infringements.

There are many stories: copyright claims on white noise, on bird noises, on public domain recordings, etc. But even if these infringements are important to note to realize just how far the absurdity of current copyright goes, Content ID has become an easily accessible tool that allows everyone to protect their rights.

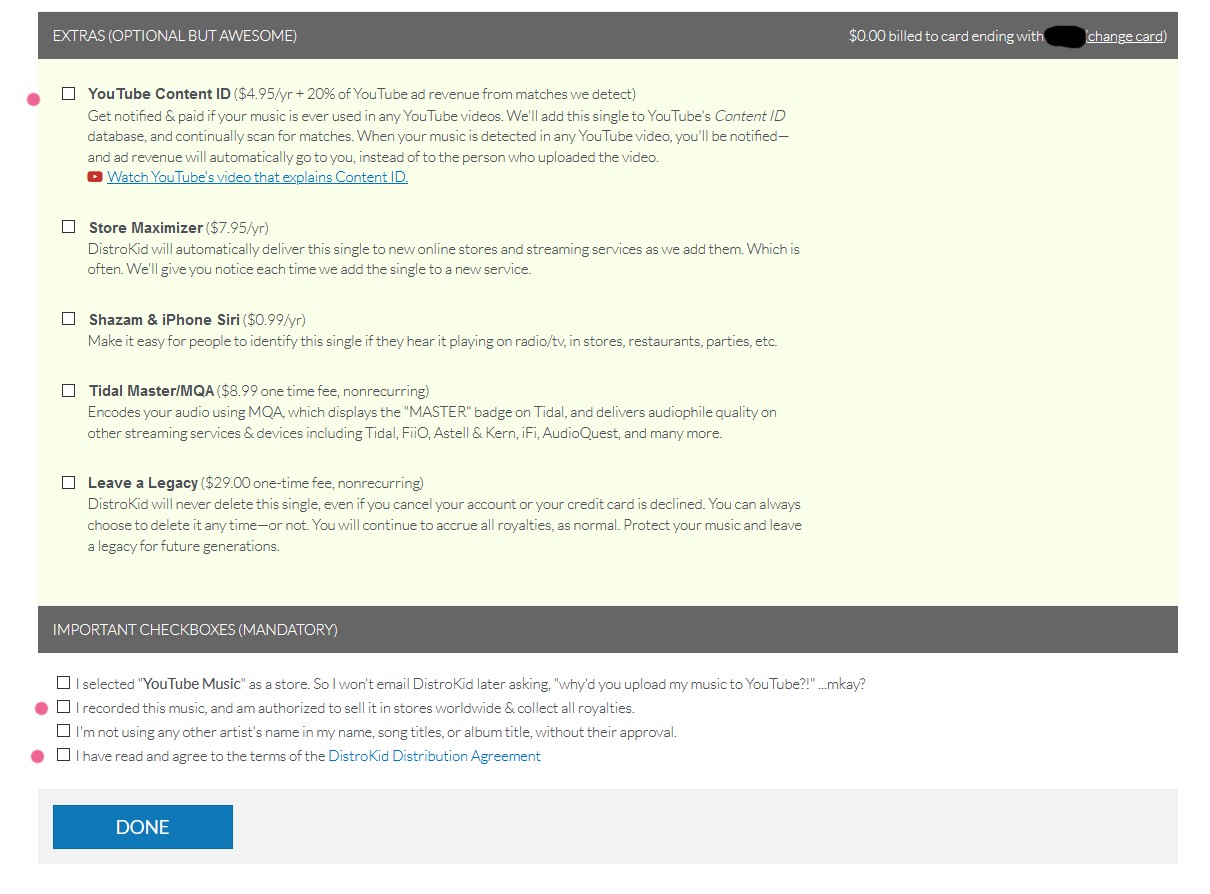

Boxes to check to activate Content ID and certify on our honor that we own the music on the website Distrokid.

There’s indeed nothing simpler than protecting one’s music with Content ID. You just need to contact a musical distribution website, check a box to attest that you own the rights to the music you want to distribute and ask the distributor (who will then receive a percentage of the ad revenue) to register the music in the Content ID digital impression data base.

You must know now where I’m going with this: it means that basically anybody can take a piece of public domain music or free music under Creative Commons license and apply Content ID to it. This is illegal because, I repeat, Content ID can’t be used on content with nonexclusive rights of use. And this happens to be the case for any content under Creative Commons or from the public domain or any other license produced by “Royalty Free” content website.

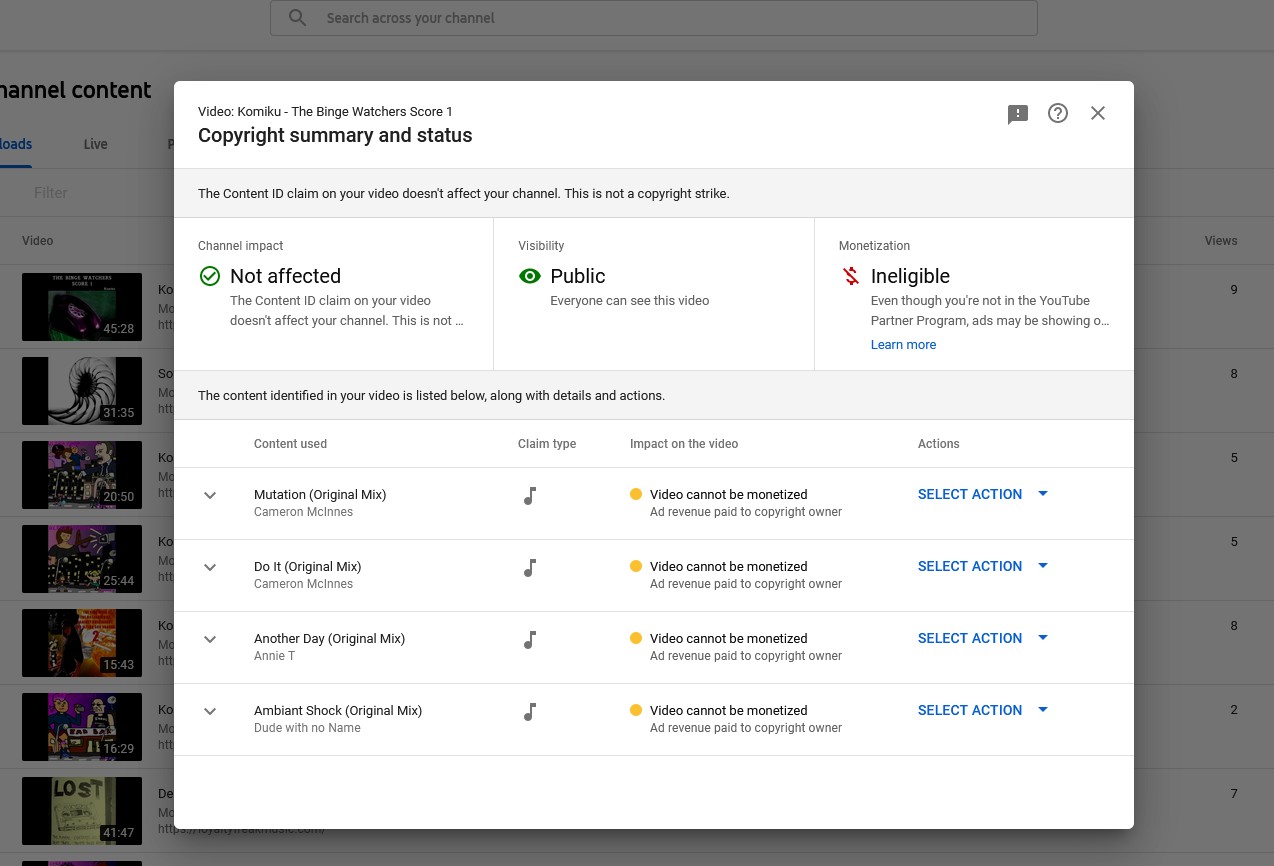

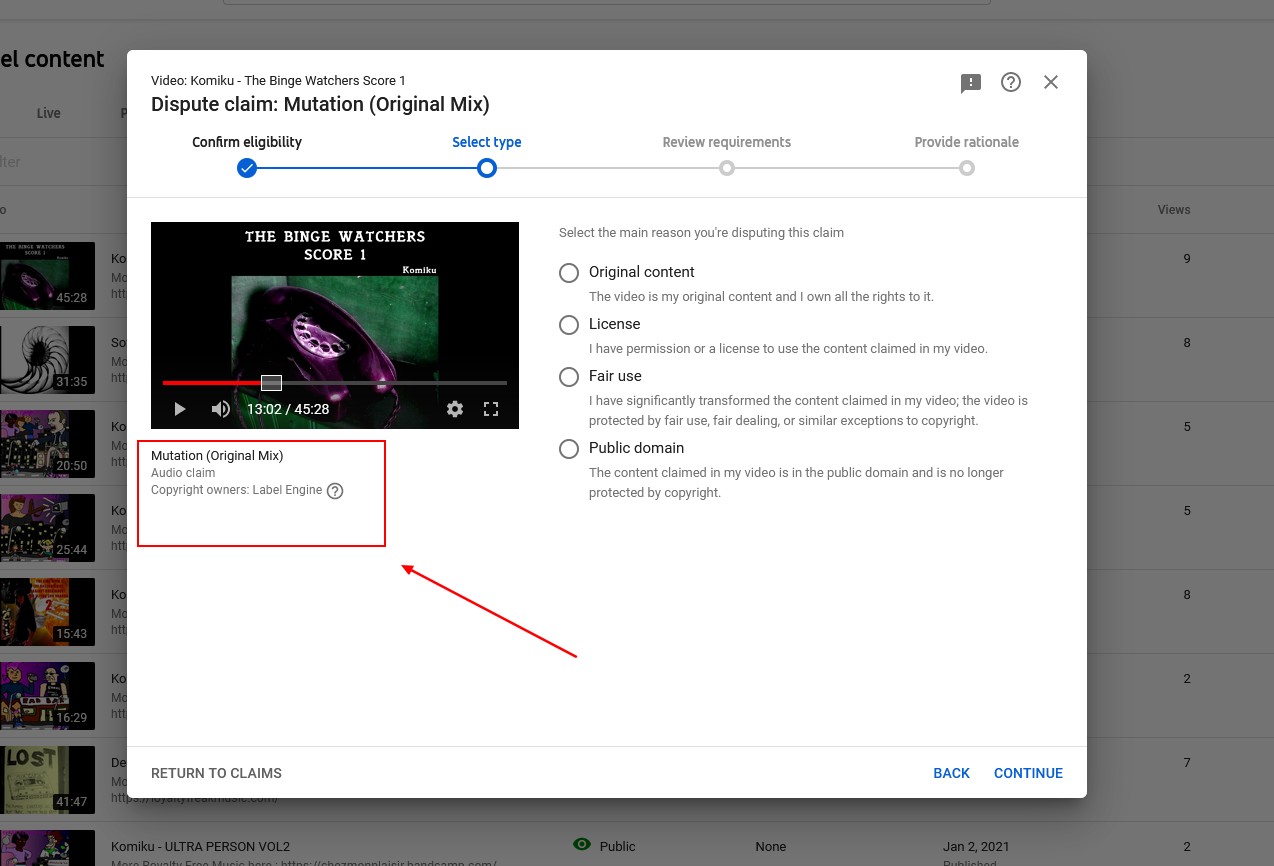

Over the course of my free music creator career, I encountered Content ID related problems many times. My music is under the Creative Commons 0 License and available on free music streaming websites such as Free Music Archive or part of free music packs on the website FreePD. It is easily accessible… and just as easily appropriable. I haven’t gone a single month without receiving warning messages or noticing for myself copyright claims on music I created. These claims are visible, notably on the YouTube Studio section of my YouTube Channels. I then have to go under: Action → Contest → to get the name of the distribution service (on the following picture, it’s Label Engine) that allowed the activation of Content ID and collects the ads revenue on the account of the person who claimed the music (in this case the artist Cameron McInnes).

Screenshot showing the steps to get the name of the distribution service and contest the copyright infringement.

However, it is not enough to contest copyright infringement if you want to end the use of Content ID on this music. It only solves the problem for this specific video. The « easiest » way to solve the problem is to directly contact the distribution services. But they’re numerous and it’s not so simple to contact them, especially if you’re not an English-speaker. Sometimes you get lost in the Q&A labyrinth and you have to fool the system to send the question you need to ask. You can also use the Terms of Use to get the legal e-mail address of the website.

In my investigation, I found some distribution services were more or less difficult to access. Among them, those which appeared the most were Daredo (which became Yomu distribution), Label Engine, United Masters, CDBaby, Amuse, State52 Conspiracy and FUGA Merlin.

The average delay to get an answer is around two weeks. Sometimes more when it’s the first time you have to deal with them. And more often than not, the first email is not enough to settle the issue.

It’s not simpler to find the problematic artist. The artists’ names used by the people who steal music to apply Content ID on it are very obscure and unknown to search engines: Stranger Group, Dude with no Name, Pollie Pop, Cameron McInness, Gadget Inc, Delude, Kkomplex, Phreaker, Abstract Normality, to only name some that I was able to identify. You can find them if you know how to use a search engine, but the problem is that these artists have no pages with their contact information.

Sometimes, you can get lucky and find pseudo labels. I did a reversed-image search on an album cover that kept appearing for various artists and I found a British label with a Facebook page and contact information. The manager of the label told me that they were unaware of the fact that putting Content ID on music could be a problem. He was convinced that the music was copyright and license free. “The music in question was purchased legally from www.fiverr.com and we were informed it was "Royalty Free" and free to re-sell, it was clearly marked royalty free hence why it has been distributed via *the music label* ».

He then sent me a link to the pack on Fiverr.

If you’re not familiar with Fiverr, it’s a website that emulates a marketplace for independent workers. You can find various services: I personally focused on the sale of music packs called « Royalty Free Music Pack », « Free music pack » or « No copyright music Pack ». There are many of them, but you have to sort through it and find the people who sell them.

When you look at these offers closely, you can notice that there’s rarely a mention of a license and never the origin of the music.

Descriptions of free music packs. Some of them mention a license, others only describe the audio content of the pack.

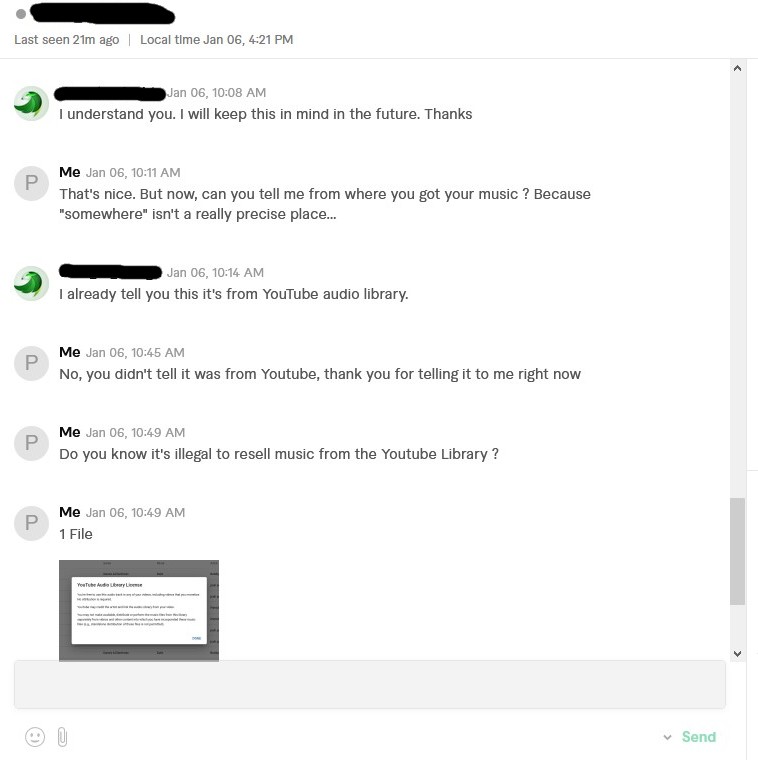

I contacted about ten sellers of these packs, asking if they composed all of their music. All of them answered that they had not. That they bought it from other sellers or found them on the Internet. None of them gave me the exact page where they found the music except for one who admitted after a long discussion that he got the music “somewhere” but also on “YouTube Audio Library”.

Screenshot of the discussion with the seller who admitted he took music from YouTube Audio Library

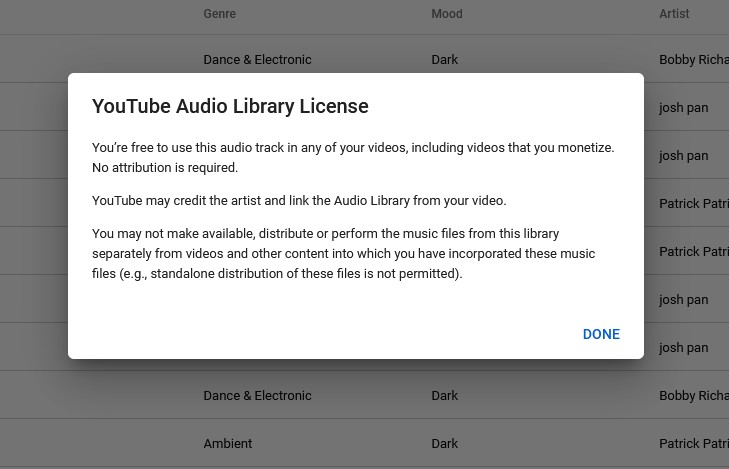

Screenshot of a YouTube Audio Library license mentioning that the distribution of these music pieces outside of YouTube videos is not allowed.

When asked to tell what license applies on these music pieces, most of the sellers answer by offering to give me a few pieces to check if they activate the Content ID on YouTube. Considering that it’s not a legal proof, I ask about the license title.

When I ask them if the music has been stolen on Soundcloud or Bandcamp, they answer that the music comes from a renowned source that allows the resale of these music pieces. They don’t tell me which source exactly.

It’s on Fiverr that I discover the PLR (Private Label Rights) license, which allows people to resell creators’ works to individuals. The journal Actualitté published an article covering this subject in 2011. It was specifically about the textual pollution this license engendered on the ebook market. On the Internet, you can find ebooks solely composed of Wikipedia articles. The PLR license, if not legally recognized, is a sort of white label that allows buyers to do what they want of what they buy. They can define new rules of use and then resell the creation under the same license, allowing other buyers to add their own conditions.

If this looks like a liberation of the creation just like Creative Commons, the latter includes rules and general conditions of use. As we saw earlier, Google doesn’t allow the use of Content ID on Creative Commons and products with nonexclusive licenses.

The major distinction between Creative Commons and the PLR license is philosophical. The Creative Commons license is closer to a social liberal approach of the distribution of common goods, including the remixing, monetization, and transformation of contents for everyone in a nonexclusive and, in most cases, free way. Meanwhile, the PLR license assumes that a digital creation is something to sell and to make profit from, which results in overflowing the market with unaltered copies and turning it into a libertarian economic nightmare.

The PLR license initiates a strange legal limbo. Because of it, it is indeed impossible to find the origin of the creation or its original license and to ensure the legality of the original product. One can wonder if the product hasn’t been stolen and then put under PLR license.

What’s pretty terrible is that right now there isn’t much to do to counter this, aside from asking platforms such as Fiverr to ask of all the resellers to indicate the origin of the music or its original licence to ensure that what they claim is free of use really is.

To summarize:

- Artists drop their music under Creative Commons or nonexclusive license on audio banks such as YouTube Audio Library, Shutterstock, Audiojungle, Pond5 or personal websites.

- Some people

• grab these music pieces and resell them as packs under titles such as « No copyright music », « Royalty Free music ». They rarely mention the original licenses or the origin of these music pieces.

• resell Creative Commons 0 or Public Domain content under Private Label Rights licenses (Public Domain comes with certain rights and restrictions, notably, Content ID can’t apply to it).

• don’t specify the restrictions of use of tools such as Content ID.

- Other people buy these packs and believe that they hold all the rights over this content and they try to make money out of it by contacting distributors to activate Content ID on it.

- Distribution services simply require these people to attest that they own all the rights on the music, without further verifications, and then activate Content ID on the music in exchange of a share of ad revenue or money.

- People who use content under Creative Commons licenses receive copyright claims while using free-to-use nonexclusive content.

- The same artists as in the beginning have to contact distribution services to stop the use of Content ID on their own work.

While writing this article, I had the opportunity to contact several free music artists in order for them to tell me about their own difficulties with Content ID.

- Most of them upload their music on their own Internet websites or on free music platforms such as Free Music Archive or Jamendo. The only way to know if Content ID has been activated on their music is through audience feedback. Then, they have to contact the distribution services.

- Some others upload their music directly on YouTube to see if it activates a claim with Content ID. It’s an efficient method to check it but it takes time. Uploading a hundred music pieces on YouTube to this end also has a real ecological impact.

- Lastly, some artists directly apply Content ID on their music even if this method is incompatible with the correct use of Creative Commons. They will then allow people individually to use their music for remixing or monetization if it seems to fit the requirement of their music’s license.

When I find my music in albums posted by people who abuse Content ID, I often encounter a problem. I rarely only find my music on these albums. There are other people’s creations and they also have been blocked in the process. In this case, I always ask the distributors to retrieve Content ID on the full album and not only on my music. The problem is that I don’t know every free music piece ever created and I never find the original creator of the music that’s been put under Content ID along with mine. I can’t warn them.

Another tool like the proprietary application Shazam (which has a quasi-monopoly on musical recognition— remember threats from Shazam lawyers received by Roy Van Rijin while he was developing a musical recognition tool that he wanted to share as an open source) could be useful to find free music creators. But like Content ID, this musical recognition is not free and is only accessible through distribution services.

We desperately lack institutions to defend Public Domain and free-license contents. There are organizations to defend free software, but the websites and places solely devoted to free music culture become increasingly rare. And their conditions are poor. There’s Dogmazic in France, Free Music Archive which had to close in 2018 because of a lack of funds and was bought and refurbished by the social network society for free music Tribe of Noise. Some other smaller websites exist but nothing that could federate and help develop tools to defend the nonexclusivity of resources under free-licenses or public domain.

Acknowledgements : Thanks to Hessel and Meghan from Free Music Archive/Tribe of Noise, Sarah Pearson from Creative Commons, free music composers who shared their experience with me, and my proofreaders: Redmarmotte, Yseult, Rob, Clémentine and Louima. Huge thanks to Theo and Abby for the translation.

[EN]Want to leave a comment ? You can write it in my guestbook !

[FR]Tu veux laisser un commentaire ? Tu peux le faire sur mon livre d'or !